First beginnings

Fricke’s interest in music and film manifested itself at the end of the 60s in his work as a journalist for the Süddeutsche Zeitung where he was offered a job by Roland Kaiser who was convinced of his journalistic talents.

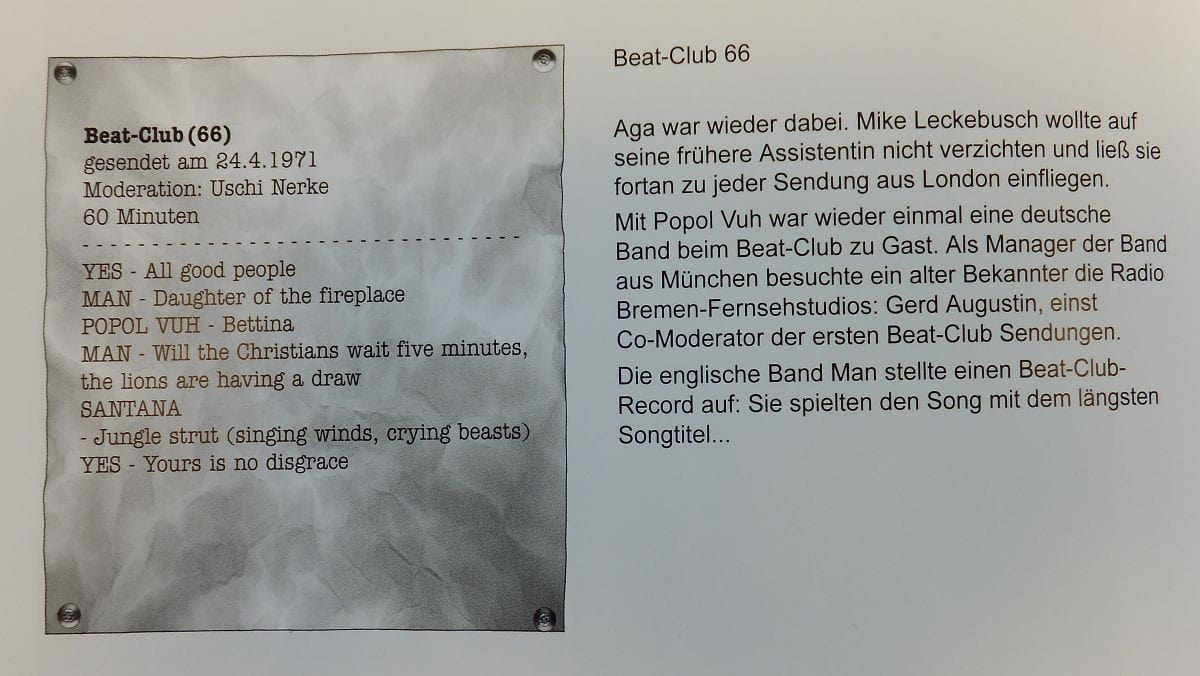

Contrary to what many think, ‘Aguirre’ is not the first experience for Fricke as a composer of film music. The film ‘Wintermärchen’(1971) by Ulf von Mechow also features music by Fricke. Besides Siegfried Schwab, The Schlippenbach Family and Antonio Vivaldi, Popol Vuh is listed for the soundtrack. Whether the film contains unique music by Popol Vuh remains a question.

The name of Florian Fricke is also listed as composer (‘originalmusik’) for the 1971 tv-film ‘Antarktis’ by Georg Moorse. The same unanswered question here: does the film carry unique music by Fricke...?

In the same period Florian contributed some unique moog music for the Werner Herzog film ‘Auch Zwerge haben klein angefangen’. Listed for the soundtrack is Florian Fricke.

These three films were released in 1971 and produced when Fricke was experimenting with the Moog. I stick to the hypothesis that Fricke made some of the results available for these three films and that all three movies carry unique material.

Questions about the involvement of Frank Fiedler and Holger Trülzsch also remain unanswered. ‘Antarktis’ and ‘Auch Zwerge haben klein angefangen’ list Florian Fricke, ‘Wintermärchen' lists Popol Vuh.

A look at GEMA (Society for musical performing and mechanical reproduction rights) learns that the track ‘Antarktis’ is listed (duration of the track: 10:00). Also music for ‘Auch Zwerge haben klein angefangen’ is registered under this same name (duration; 8:00). The music for ‘Wintermärchen’ however has not been registered at GEMA. But maybe it is listed under a so far unknown name.

Lebenszeichen

"In Lebenszeichen sieht man neben Wolfgang von Ungern-Sternberg in einer kleinen Szene auch Florian Fricke, Werner Herzogs wohl liebsten Freund. Er hat einen Kurzauftritt als Pianist. Der 2001 im Alter von nur 57 Jahren verstorbene Musiker prägte mit seinen sphärischen Kompositionen viele von Herzogs Filmen. Kennengelernt hatten sich die beiden 1966 in München, nachdem Herzog aus Amerika zurückgekehrt war. Man mochte sich, spielte zusammen Fußball, unterhielt sich über jeweilige Projekte – und beschloss schließlich die erste Zusammenarbeit bei Lebenszeichen. Florian Fricke und dessen spätere Frau Bettina von Waldthausen gehörten zum Team. Sie fuhren mit zu den Dreharbeiten nach Kos, wie sich von Waldthausen, die damals die Standfotos für den Film machte, erinnert: “Da musste jeder für alles und alle mitarbeiten, immer für das Ganze. In dieser Intensität ist das später nie so gewesen. Lebenszeichen war eben ein Pionierfilm, das Debut von Werner. Er hat immer sehr viel Wert gelegt auf den Spirit, auf den Teamgeist, man sollte nichts auslassen – von den Vorbereitungen bis zur Premiere. Es ging um eine hundertprozentige Präsenz. Florian und Werner waren dabei auf eine Art Konkurrenten und Inspiratoren. Während Lebenszeichen unternahmen die beiden viele, viele Spaziergänge, auf denen sic sich austauschten, wie der Film weitergehen solle. Sie ergänzten sich schön. Vermutlich deshalb hat es Florian später auch so gut verstanden, die Musik für Werners Filme zu machen. Er wusste, was der brauchte. Die Musik war immer schon vorher da. Florian hatte, wie ein Zauberer, einen großen Kasten, seine magsiche Box, mit lauter Tonbandschnipseln drin. Die haben die beiden sich dann angehört – und Werner fand meist sehr schnell etwas unter den vielen Schnürsenkeln. Er hatte ein gutes Gespür für Musik. Und Florian spürte eben intuitiv, was Werner wollte”.(Moritz Holfelder, Werner Herzog die Biographie, 2012, p.119)

Aguirre

It all really started with the soundtrack for 'Aguirre'. This was the beginning of a long and fruitful cooperation between Herzog and Fricke. The story how this collaboration came into being is told many times by Fricke:

Florian Fricke: "Ich kenne Werner schon lange bevor er einen Film gemacht hat und bevor ich Musik veröffentlicht habe. Damals gingen wir schon pläneschmiedend als Freunde durch die Straßen. Dann haben wir uns in gewisser Weise aus den Augen verloren. Erst als Werner zu 'Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes' Musik suchte (zunächst in Rom im Archiv von Ennio Morricone), sagte ein gemeinsamer Freund: Das kann nur den Florian machen! Werner Herzog: Na, den kenne ich doch! Dann rief er sofort an und ich fuhr runter nach Rom". (E.Schneider, Handbuch Filmmusik 1, 1986, p.59)

Or in the 1989-interview by Ian Laycock:

Florian Fricke: Werner Herzog had finished filming Aguirre and was in Rome doing the English sync for the film. He was desperately looking for suitable music. He tried with Morricone but couldn't find anything suitable for the film and was very unhappy about it. He was living in an albergo in Rome and was eating there one evening with a young actress from Germany. The conversation finally got round to this problem, that he couldn't get the right music and she said, "There's only one person, really, and that's Florian". So he rang me in Munich, I went to Rome and he showed me the film. I went home and wrote the music and from that point on I was the composer on Werner Herzog's films.

For Keyboards:

Keyboards: Schon recht früh, nämlich so ab 1972, begann deine Zusammenarbeit mit dem Filmemacher Werner Herzog, eine Kollaboration, die den Namen Popol Vuh auch über den Kreis der blossen Musikkonsumenten weit hinaus bekannt machte. Von 'Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes' über 'Herz aus Glas', 'Nosferatu' bis 'Fitzcaraldo' und 'Cobra Verde' hast du die Musik für Herzogs Filme geliefert. Wie begann eigentlich eure Zusammenarbeit?

Florian Fricke: Das hat - wie eigentlich alles im Leben - einen ganz normalen und unmystischen Anfang. Herzog war damals für die Synchronisation van 'Aguirre' in Rom und suchte eine passende Musik bei Ennio Morricone und fand sie nicht. Eine gemeinsame Bekannte machte Herzog auf mich aufmerksam. Er rief mich später in München an, und zwei Tage später war ich in Rom und habe mir den Film angesehen. Zurück in München habe ich dann eine Musik dazu angefertigt, die Werner Herzog auf Anhieb gefiel. Seitdem gibt es die Zusammenarbeit. So einfach war das.

On two places in 'Herzog on Herzog', Herzog explains that he had a clear picture of the music he wanted for his Aguirre-film:

"Whenever you hear silence, you know there must be indians around, and that means death. We spent weeks recording the birds and the soundtrack was composed from eight different tracks. There is not a single bird that has not been carefully placed as if in a big choir. For the music, I described to Florian Fricke what I was searching for, something both pathetic and surreal, and what he came up with is not real singing, nor is it completely artificial either. It sits uncomfortably between the two". (p.80)

"In Aguirre I wanted a choir that would sound out of this world, like when I would walk at night as a child, thinking that the stars were singing, so Florian used a very strange instrument called a 'choir-organ'. It would sound just like a human voice but yet, at the same time, had a very artificial and eerie quality to it. Florian was always full of ideas like this" (p.256) From what Herzog suggests above, one is inclined to conclude that Fricke may have directed his attention to the choir-organ as a fitting instrument for realizing Herzogs vision. This instrument was played at that time by Jimmy Jackson in Amon Düül 2.

On August 24th, 1972 Florian Fricke signed a contract with Werner Herzog Produktion. It opens as follows: “Popol Vuh ist der Produzent mehrerer Musikstücke unter dem Sammeltitel ‘Lacrime di Re’, die am 23.8.72 in München auf Band aufgezeichnet werden.” Recordings took place one day before the contract was signed. It says that several pieces of music where recorded, altogether named ‘Lacrime di Re’. The contract also speaks of ‘Träne des Königs‘ instead of ‘Lacrime di Re’, both meaning ‘Tears of the King’. The contract allows Werner Herzog Produktion to use the music also for future films. Which he did. The music was also used for the documentary ‘Die Große Ekstase des Bildschnitzers Steiner’ (1974) and probably also for ‘Herz aus Glas’(1976).

What did Fricke actually compose when he got back from Rome. For sure there was not much time left for him, as Herzog was nearly finishing 'Aguirre'. In answering this question we will also answer two other ones: what music do we actually hear in the film? Is it identical with the music on the original album that appeared in 1975? Most of the music on the soundtrack-lp is not used for the film: 'Morgengruss II', 'Agnus Dei' and 'Vergegenwärtigung', do not appear in the film. The remaining pieces 'Aguirre I' and 'Aguirre II' do return in the film. Both pieces are very similar, and only their codas differ.

Since the SPV-rereleases are out we also know of 'Aguirre III'. Comparing the three versions one can conclude that Fricke did a lot of editing and mixing.

On two moments in the film an actor plays a tune on panflute. In other parts of the film we hear the theme again without seeing it played by the actor. The tune is played in slightly different versions. It's also on the soundtrack as the second part of 'Aguirre I'. After the choir-organ is faded out after about 6:10 minutes the panflute sets in after a short silence.I think it is safe to say that this tune is not played by a Popol Vuh member, but that it is taken from the film. On many moments in the film we hear a very peacefull guitarpiece. Alas this is not on the soundtrack, nor on any other Popol Vuh record.Also one can hear one or two other flashes of Popol Vuh music that I cannot identify and that are not on any record as far as I know .

There are two scenes in the film with tribal percussion music. I suppose they are taken from an ethnic recording. In any case, they are non-Popol Vuh.

So, I think it is a fair to conclude that only the 'Aguirre'-theme, plus the quiet guitar-interludes were intentionally composed by Fricke for the film.

‘Aguirre, der Zorn Gottes’ was premiered in Germany a few months later (December 29th, December 1972) and first shown on television on January 16th, 1973 (ARD). The public however ignored the film. This changed after the film was shown at Cannes Festival in 1973 and received good reviews. From February 1975 onwards, the movie was shown for months, day after day, in two movie theatres in Paris. This led to the return of the film in the German movie theatres in 1976.

In an interview for SWF III (1974) Fricke explains about future plans: “Das ist ein Teil von dem Aguirre der Zorn Gottes, dieser Filmmusik von uns, die sehr gut angekommen ist. Es wurde sehr viel gefragt, ob da auch Platten erscheinen. Die werden wir da verwenden und eine neue Seite aus der Bergpredigt, verschiedene Sachen.” At that moment he had a split-lp in mind. The Aguirre music - “that was very well received” Fricke adds - on one side and music inspired on ‘Der Bergpredigt’ on the other. It became however two separate albums: ‘Seligpreisung’ and ‘Aguirre’.

Considering the tracklist it is not unlikely Popol Vuh nor the recordlabel had the release of a soundtrack in mind. It is plausible it is an ad hoc selection. Both ‘Morgengruss II’ and ‘Agnus Dei’ were recorded after the film was completed. The lenghty Moog-piece ‘Vergegenwärtigung’ on side 2 has no reference to the film.

Panpipe

In two scenes in the movie a Peruvian musician plays a tune on a panpipe. In his book ‘Aguirre, Wrath of God’ (BFI, 2016) Eric Ames writes concerning this tune: “The uncredited tune comes from ‘Cholitas Puenas’, a traditional Peruvian song as arranged by Moises Vivanco and sung by Yma Sumac since the 1950s. When the source was brought to his attention, several years after the film’s release, Herzog claimed ignorance, requested permission and paid for the rights to use it”(p.93). This is in line with my findings at the Deutsche Kinemathek (Werner Herzog Archive). In a letter dated March, 16th 1976, GEMA reported to Herzog: “Anlässlich der Vorführung in einem Madriater Lichtspieltheater hat der Spanische Komponist Moises Vivanco mit absoluter Sicherheit feststellen können, dass sein Werk ‘Dance of the moon Festival’(Cholitas Puenas) mehrmals zu gehör erlangt.” In his answer of March 20th, 1976 Herzog explains that they met the panpipe player at the marketplace of the Peruvian city Cusco. He was asked to improvise a melody for a specific scene in the movie. Herzog had no idea he was paraphrasing an existing composition and agreed on paying the rights.

On both the Italian as well as the French edition, the panpipe-theme is integrated as a coda to ‘Aguirre 1’.

Collaboration Werner Herzog – Florian Fricke

Next some quotes that illustrate the collaboration between the two.

First a quote from: 'Werner Herzog in Bamberg - Protokoll einer Diskussion 14./15. Dezember 1985" (Herausgegeben und eingeleitet von Andreas Rost, Bamberger Studien zur Kunstgeschichte und Denkmalpflege, p.154-156):

Frage (Robert Gerlach); Ich hätte noch eine Frage zur Musik. Sie nehmen meinetwegen im Film immer verschiedene Drehorte, nur als Beispiel, aber in der Musik sehe ich eine gewisse Konstanz, also es taucht ja häufig die Gruppe ‘Popol Vuh’ auf. Da wurde mich zum einen interessieren, warum immer ausgerechnet die Gruppe, die ja eigentlich inzwischen gar nicht mehr so aktuell ist, und dann, inwieweit durch die Musik so eine gewisse Konstanz in den Film kommt, die meiner Meinung nach zum Teil auch unpassend an manchen Stellen ist – z.B., wie wir vorhin gesehen haben, in HERZ AUS GLAS, wo die Landschaftsbilder, in denen Hias den Berg runterging, von dieser leicht fröhliche Musik meiner Meinung nach zerstört werden.

Herzog: Das empfinde ich nicht so. Eigenltich eher ganz anders. Zu dieser Gruppe ’Popol Vuh’: das hat mich nie interessiert, ob die gängig ist oder nicht, das ist ja im Grunde eh nur einer person, der Florian Fricke. Ich habe mit ihn gearbeitet, weil ich mich da sehr gut habe verständlich machen können, was eigentlich die Musik sein sollte, und da sind ja auch sehr schöne Sachen immer wiedergekommen. Ich glaube, das ist nur deswegen ausgewählt , weil für meine Begriffe und meinem Empfinden nach die Musik eben dort fast ideal ist. Ich könnte mir eigentlich gar nichts anderes dafür vorstellen. Vieles ist auch nach einer bereits vorhandenen Musik gemacht worden, da hat es also Musik gegeben, und danach sind sozusagen die Bilder organisiert worden, d.h. der Schnitt nach der Musik. Ich kann nur grundsätzlich sagen, ob die Musik jetzt da paßt oder nicht, darüber läßt sich überhaupt nicht argumentieren. Ich nehme nur zur Kenntnis, dass Sie es nicht als passend empfinden an dieser Stelle; ich kann nur sagen, ich empfinge es richtig. Ich selber kann mir gar nichts anderes vorstellen. Es ist im übrigen auch sehr viel rumprobiert worden. Es kommen auch Musiken vor bei mir, wo ich niemals gedacht hätte, daß sie je in einen Film hineinpassen würden. Und trotzdem passen sie auf einmal.

Frage (Robert Gerlach): Aber dass so eine Musik jetzt etwas Bestimmtes signalisiert, z.B. bei Aguirre und beim Bildschnitt zu Steiner, da wird, glaube ich, teilweise dasselbe Musikstück verwendet, wenn ich mich nicht irre. Herzog: Das kann sein, ja. Ich glaube ja, daß es an einer Stelle mal sowas gibt. Fragender: Ist das Zufall, oder...?

Herzog: Das ist in dem Fall Zufall, weil wir alles mögliche durchprobiert haben und zufälligerweise lag noch irgendeine Rolle von Musik auf Perfo-Tonband von Aguirre herum, und ich habe gesagt: “Probieren wir doch mal alles von da durch, da war doch irgendsowas.” Und auf einmal hat das unheimlich gut gepaßt. Also das ist sehr oft einfach eine Rumtasterei, wie Arbeit in einem Schneideraum halt funktioniert. Gerade zufälligerweise ist noch ein ungelöschtes Stück von einer solchen Musik da, und man probiert es einfach aus, im Verlauf von 20 andere Musiken, die man auch durchprobiert hat. “

*

Keyboards: Filmmusik, so wird gesagt, ist immer dann am besten, wenn man die vom Film gelöst wird, gar nicht erkennt. Wie sah konkret eure Zusammenarbeit im Einzelnen aus?

Florian Fricke: Das war seht ununterschiedlich. Das einzige, was immer geleich war, war die Terminnot. Wie viele andere Regisseure auch, kam Herzog strets kurz vor Torschluiss, wenn die Kinotermine schon gebucht waren, and und sagte: >Jetzt muss ganz schnell die Filmmusik gemacht werden=. So waren das sehr intensive, weil unteer hohem Druck entstandene Produktionen.

Andererseits kam er auch gelegentlich und sagte: 'Florian, mach deine Kiste auf und spiel mir vor, was du an neuer Musik hast'. Das war zum beispiel bei 'Fitzcaraldo' so. Die Musik wurde nicht speziell für den Film gemacht, sondern war bereits auf der Platte, 'Sei still, denn ich bin' veröffenlicht worden. Herzog fischte sie aus meiner Kiste, hob den Zeigefinger und sagte: 'Diese Musik will ich Haben!'

Die Arbeit mit Herzog war für mich immer interessant, weil ich in ihm einen ausserordentlich schöpferischen Menschen mit enormem Arbiets-Ethos kennengelernt habe, der beim Drehen immer für eine Überraschung gut war. (p.22-24)

Werner Herzog has not uttered himself very often about his collaboration with Fricke. But here are some quotes that illustrate the importance of Fricke for Herzog:

"Florian was always able to create music I feel helps audiences visualize something hidden in the images on the screen, and in our own souls too." [ Herzog on Herzog, p.256]

Werner Herzog: The music in my films is also very much neglected, if I may interrupt you, in Germany as well. Since AGUIRRE, my friend Florian Fricke, has done the music for almost all my films - for STEINER, for LA SOUFRIERE, for STROSZEK, and for HEART OF GLASS - and I've tried to push very hard so that he would be given the National Film Award this year. They've never given it to him, and there has been complete neglect of his work. Not even a single mention! And this year they just by-passed him once again! [From: Images at the Horizon]

Herzog mistakenly mentions La Souffriere and Stroszek here, and forgets 'Auch Zwerge' and 'Nosferatu' .

From a dialogue between Jonathan Demme and Werner Herzorg on june 5, 2008 - celebrating the launch of Moving Image Source, a museum website devoted to he history of film, television and digital media - we learn:

Demme: That reminds me about Aguirre, and a question. Popol Vuh, who was credited with the score of a number of your films around that periodCCI know there are roots to this nameCCis that a band?

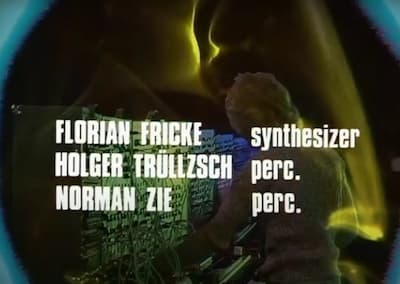

Herzog: Yes, a band which was basically one person, Florian Fricke, who unfortunately died three years ago. [He was] a close friend of mine who was a prodigy as a piano player, but had to give up a very promising career because he had inflamed ligaments, and became a composer. He named his group - which was mostly him, because he played many instruments parallel, and recorded it on parallel tracks, and a few other musicians - he named it after the sacred text of the Kaqchikel Maya Indians, the Popol Vuh, the book of - Buch des Gottes [Book of the Gods] - well, I can't translate it right now. It's one of the very, very beautiful and important texts for me, and I gave it to him to read. Actually Lotte Eisner, the great film historian, reads some of Popol Vuh as a text for Fata Morgana (1971). That's the context. Popol Vuh comes from this book, which was very important for me; I kept reading and re-reading it, and gave it to him; and he named the group Popol Vuh. We had a very, very fine rapport about music, and he was very important for me. Then later on, after about ten or twelve years of collaboration, we slowly drifted apart because he was moving very much into a pseudo-culture of "new age," which I can not stand at all. (Laughter) I still loved him, but I moved into some sort of a different direction. The style of his music was more and more influenced by a babble of pseudo-philosophy. So that was the reason why our collaboration drifted apart; we stayed friends until he died.( From: movingimagesource )

For the booklet included in the SPV-reediitons Werner Herzog wrote a short In Memoriam:

In Memoriam Florian Fricke

Jokingly, we often said that he must never grow old, he who looked like a youth as we know them only from ancient Greek statues. Now he is with us no longer, and it=s like a tear right through the heart that Florian Fricke died much too soon. To me, Klaus Kinski was myu dearst enemy, my best feiend so to speak, but Florian Fricke kept the balance, he knew a safe way across the abyss: when it came to creative work, he was my dearst friend.

And yet - regardless of outward appearance - he was a highly complex being, inticately spun and vulnerable, like a spider=s web. In reality, he was a poet first and a musician second, a composer. His feel for the >inner=narrative of a cinematic story was infallible., and his music had the ability to change our perspective as onlookers, even though a picture always remains the same projection of light in the cinema. He made visible what would otherwise have remained mysterious and forever hidden in the images. What is more, he had a talent for compising music that created whole new spaces, in concrete terms: landscapes that gain an unknown dimension which would not be accessible otherwise.

Only recently I came across a wonderful piece of music by him, which I had the privilige to use in a new film - grand orchestra, choir, and among the choir also his voice. I hear it sounding so clear and isolated as if he was the only singer, as if he were standing next to me.

Deeply moved, I tried to persuade myself it was only a rumour that Florian is no longer on this planet, but then a strange certainty prevailed: in a way he is till among us, with his voice, his music - albeit hidden, distant. He has not truly left us.

Werner Herzog

In an interview by Jason Gross for online music magazine Perfect Sound Forever (august 2013) Bettina von Waldthausen reflects:

PSF: Could you talk about Florian's working relationship with Werner Herzog? How did they get along? How would Florian figure out what was the right music for the movie soundtracks? Did he have a particular favorite?

BW: There is so much written about Werner and Florian's collaboration that there is not really much to add. They were friends from youth and both very opposite strong characters, each of them a magician. Werner with his beautiful unique archetypical movie/pictures, Florian with his unique magical sound. As far as I remember, Werner came into Florian's studio to listen to the latest recordings, and most of the time he found soon what he was looking for. In some cases, like for instance Cobra Verde, music had to be completed afterwards. But most of the time, the tracks were already there, before the film was done. I don't think, he had a particular favorite. You go with the path. When the work is done, you take the next step on your inner path. He only listened to the recordings- that he was just working with - for hours, day and night.

*

Die Zusammenarbeit von Werner Herzog und Florian Fricke beruht nicht weinig auch auf einer geistigen Nähe: Werner is früher auch immer an interessanten exten interessiert gewesen, z.B. auch an den ‘Popol Vuh’-Texten, den Wechselreden von christlichen Geistlichen und indianischen Priestern aus Guatemala. Das sind unglaubliche Texte, auf denen unter anderem die innere Verwandtschaft zwischen uns beruht. Unsere Zusammenarbeit harmoniert auch deshalb, weil ich seine Filme mag. Man muß den Film mögen. Werner sagt: “Um das Projekt muß ein heiliger Bezirk sein.” Da sind wir uns sehr nahe. Dann kann man die Arbeit beseelen. Man muß überzeugt sein. Das bin ich von Werner Herzogs Sachen.s istfür mich schön, für ihn Musik zu machen. Die Identität zwischen uns, die kommt vom inneren Verständnis her. Wir brauchen uns deshalb nie groß und langwierig abzusprechen. Für Werner ist es wichtig, daß man ganz genau versteht, was er in dem Film sagen will. Dann gibt es höchstens kleine Strukturhinweise von ihm; z.B. mag er keinen Rhythmus, nur Zeitloses, - das ist für mich dann ein Anhalt. Da ich aber selbst zeitlos komponiere und kein anderes Interesse habe, trifft sich das sowieso.”

Florian Fricke komponiert seine Musik weit weiniger als andere Komponisten nach bestimmten Längen oder für bestimmte Stellen des Films. Oft wird auch bereits komponierte und auf Schallplatten bestehende Musik genommen: “Da kommt Werner manchmal auch einfach an und sagt: ‘mach deine Kiste auf!’ Dann hört er sich meine Musik an und läßt sich inspirieren, schon während er am Drehbuch schreibt. Er meinte mal, ich wäre immer zwei Schritte voran. Es hat sich auch schon ergeben, daß nach einem Musikstück eine Szene entworfen wurde. Ein Musikstück, das zum Beispiel unabhängig vom Film von mir schon vorher auf Platte produziert war, war das Gitarrenthema (das Thema von Lucie und Jonathan) in ‘Nosferatu’. Die Platte hieß ‘Brüder des Schattens, Himmel des Lichts’ und enstand, als ich aus dem Himalaja zurückkam, gut beieinander von einer langen Wanderung. Zunächst hat es mir gar nicht behagt, daß er die Musik hineingehängt hat in diesen Schauerfilm. (Angstmusik mache ich nie!) Aber sie paßt. Obwohl sie gar nicht dazu gedacht war". Vorproduziert war auch die Musik zu Herz aus Glas. Die wichtigen Teile daraus entstammen Florian Frickes Schallplatte Singet, denn der Gesang vertreibt die Wölfe’, die er – nachdem die Musik in Werner Herzogs Film kam – in ‘Herz aus Glas’ umbenannte. Im Studio wurden lediglich noch einige dramaturgische Versatzstücke produziert.

Daß Werner Herzog auch von seinem Komponisten Musik sehr früh bestellt, liegt daran, daß er gerne auf Musik inszeniert und nach Musik schneidet. Hierauf gründet die fantastische Symbiose von Bild und Musik in seinem Filmen. Auch speziell komponierte Musik ist nie in Grenzen gesteckt, sondern sehr offen: der Ort im Film muß erst noch genau festgelegt werden. Florian Fricke: “Wenn ich im Studio fertig bin, spiele ich ihm die Musik vor. Dann weiß er für jedes Stück, wo es hinpassen könnte. Er kennt seine Stellen. Und ich habe immer irgendwie die Musik, die er braucht. Werner hat ein großes Empfinden, wo und wie die Musik angelegt werden soll. Das hat er im Blut. So wie er die Musik anlegt, holt er auch immer das Maximale su ihr heraus.” ( (E.Schneider, Handbuch Filmmusik 1, 1986, p.193-194)

Cobra Verde

"Cobra Verde war dann 1987 die letzte große Zusammenarbeit – Werner Herzog und Florian Fricke hatten sich da bereits auseinanderentwickelt, wie Bettina von Waldthausen erzählt: “Es ist ja kein Geheimnis, dass Florian sehr viele Drogen nahm und mehr und mehr in seine transzendente Welt entschwand. Und das war genau das, was Werner nich wollte. Er hat zwar auf seine Weise auch eine metaphysische Welt erschaffen, aber die ist ganz anders. Bei ihm kommt sie aus dem tiefen Unbewussten, und bei Florian entstand sie sehr bewusst aus der Beschäftigung mit dem Spirituellen. Werner entdeckte bisweilen auf der Erde den Himmel, und Florian hollte immer den Himmel auf die Erde herunter. So funktionierte das bei den beiden. Sie kamen von zwei Seiten. Lange Zeit passte das gut zusammen, sie waren sich ebengebürtig – am Ende sind sie sich aber ein bisschen fremd geworden. Sie waren Freunde und auch wieder nicht. Als Florian 2001 starb, war Werner zufällig in München, er kam sofort vorbei, war sehr, sehr betroffen – udn hat einen wunderbaren Nachruf auf Florian geschrieben. Da hatte ich dann wieder nicht das Gefühl, dass sich da was auseinandergelebt hatte.” (Moritz Holfelder, Werner Herzog - die Biographie, 2012, p.119-120)