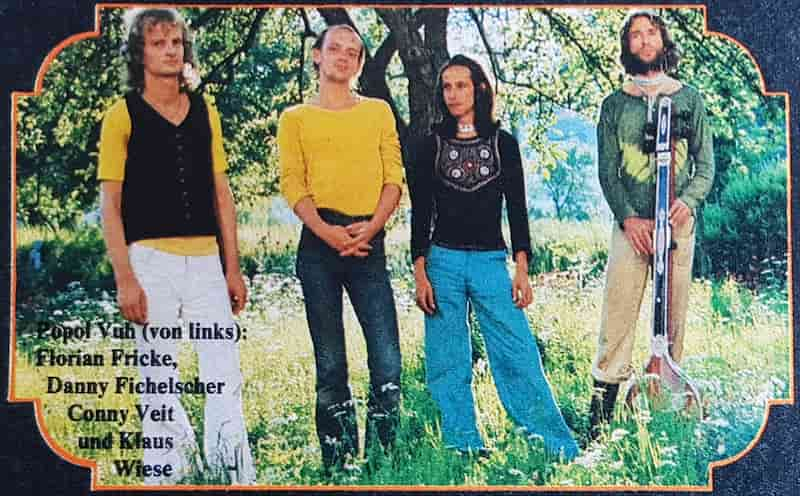

The Lindau Project interview

PRESENTING THE LINDAU PROJECT

“Why not find some people who feel some sympathy towards Fricke’s music, and play it together?” This question brought together a number of young musicians from the south of Germany at the beginning of 2024. A special initiative! We have to go back to 2006 when the Italian ensemble Ars Ludi dedicated a project to the music of Popol Vuh. Besides we have the remix exercises on 'Revisited & Remixed'(2011). Never before have we come across a project that wants to give the music a new life from a guitar-based line-up. The musicians - aptly named The Lindau Project - have been busy working for a number of months. A first sample can now be found on Youtube. With an inspiring version of 'Steh auf, zieh mich dir nach', they announce their intention to the world and manage to strike a chord. During the course of the year they will take the stage and there is a good chance that pieces will be performed live for the first time. After all, Popol Vuh has hardly performed live. High time to introduce the musicians and let them talk about their backgrounds and motives. (Dolf Mulder)

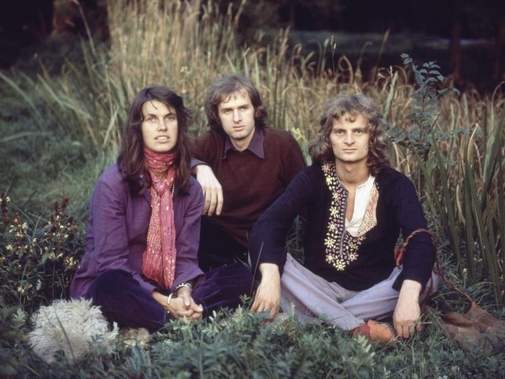

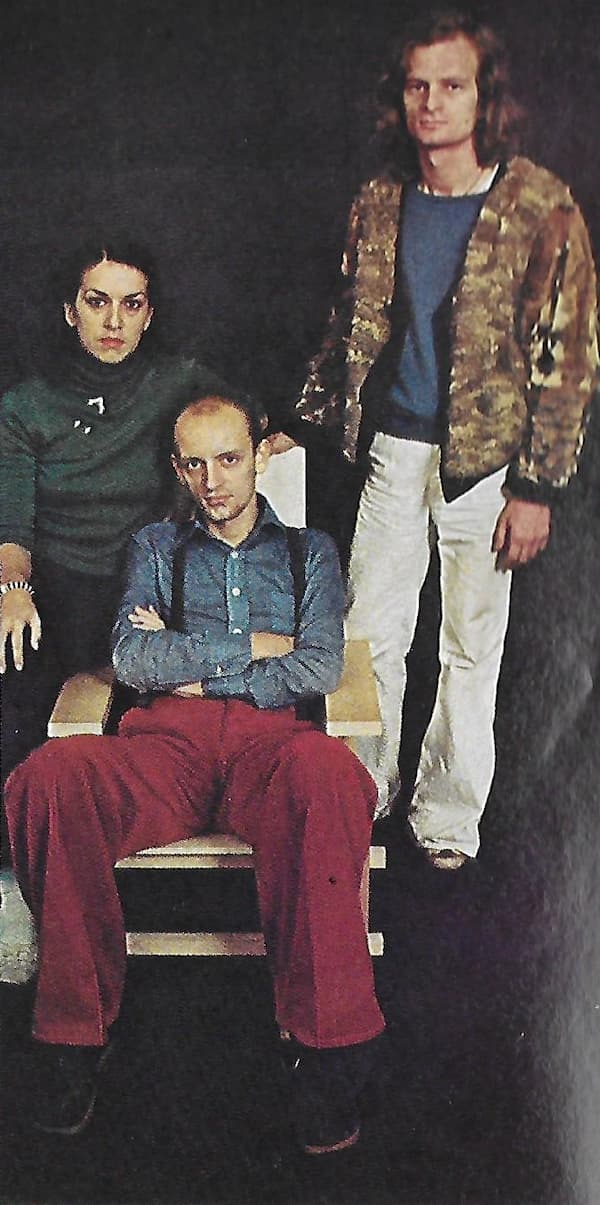

(From left to right: Luis, Amelie, Marco, Jan, Max, Fabian)

We are:

Max Bolch - electric guitar

Fabian Broicher - drums, percussion, acoustic guitar

Luis Dollinger - electric baritone guitar, drums

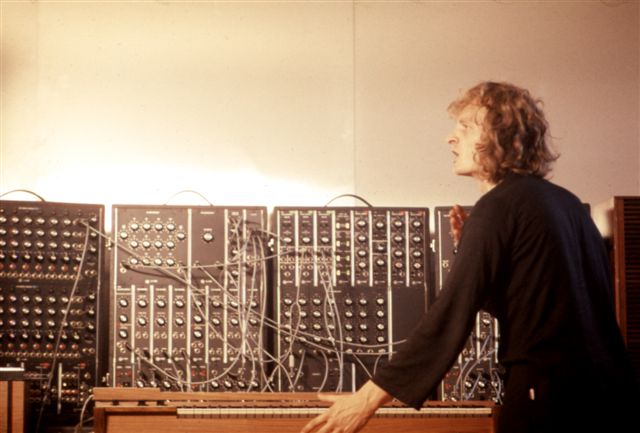

Jan Fischer - piano, moog synthesizer

Marco Grötsch - electric 12-string guitar, sitar

Amelie Klug - vocals, electric guitar, percussion

- Tell me a bit on your musical backgrounds.

FABIAN: Well, I was lucky that I grew up with lots of music around the house. My dad played the guitar, he loved King Crimson and most of the classic ‘prog rock’ bands. My mom is a fantastic creative painter, loves movies and art, so I had a very creative upbringing. I had my first drum lesson when I was six and just continued from there, always making music to some extent. But originally my drum teacher was very keen on me playing jazz and funk. It was only later in school I started playing rock – because my classmates persuaded me that it was cooler.

MARCO: Here and there and everywhere. Willingness to go beyond the orthodox and conventional is what piques my interest. That said, I often find myself more interested in the cultural, historical, and lyrical side of the music than the actual music itself. While I’ve learnt to play the guitar at a young age and took up singing later on, I went into the humanities at university, where I’ve been particularly drawn towards exploring the countercultural zeitgeist that also birthed Popol Vuh. In terms of actual playing, it’s probably folk and early folk rock that have influenced me most.

LUIS: Growing up it was also mostly rock music for me and some hip hop. Later I actively tried to get into pop music and found a lot of alternative pop, folk and indie music I really enjoy. The thing about listening to music that probably intrigues me the most is what artists today do with the possibilities and influences they have. So the experimental characteristics are what brings my love of more contemporary music and Krautrock together.

AMELIE: As a child, I grew up with my dad’s Joe Cocker CDs, and my mother’s collection of classical orchestra music. In piano and cello lessons I got educated in a strict classical style, which I didn’t like much, so I started teaching myself some guitar chords to sing my favourite pop songs to. This is what rescued my love for making music. I eventually started an acoustic songwriter pop trio as part of which I improvised on the cello, and also started performing solo as a singer/songwriter. The electric guitar is the newest in my journey and I love exploring rock and more experimental sounds.

MAX: Originally I grew up with all sorts of pop and rock music from the 1960s onward, mostly folk- and jazz-inspired English music, e.g. Fairport Convention or Caravan, and I mostly played the Hammond organ and some bass guitar. Over the years I developed an interest in European traditional folk music. This interest completely took over ten years ago, and the projects I have played in very much reflected that; in folk music I have focussed mainly on the electric guitar, besides other stringed instruments. Of course I was always aware of the existence of classical music in those years, but only a few classical compositions really influenced me consciously. Through the works of some courageous English folk musicians, foremost Ashley Hutchings, Martin Carthy and the tragically unknown visionary Royston Wood, the intersection between folk music, early music and electric instrumentation became my principal field of interest, and I locate Popol Vuh in a similar realm. (about Luis) I got to know Luis on an open stage evening in Regensburg, where - if my hazy memory serves me well - he played three songs of his own with just a guitar, a very stark and intense performance. Atmospherically it was sort of a Syd-Barrett-ish moment, although his songs are different. (about Jan) Jan plays the bass guitar, writes songs and sings in several bands in Regensburg, notably he’s Marco’s bandmate in the psychedelic/folk rock band Apollo Papillon in which they only play original songs. He also does some very interesting synth&vocal-based solo material under the pseudonym Monterry. He is not only a versatile musician, but also a wonderful sound engineer with great ears for proper microphone placement, sound design and mixing.

JAN: Musical talent in my family seems to only hit every other generation, so as I grew up I learned a few instruments, while both of my parents played none. Their taste in music is actually quite profound, but never niche. Ever since, I have soaked in every bit of music whenever I heard it and wherever I could get it from. The journey has been a wild ride, unpredictable, and I never stopped being a fan. However, the dream of becoming an artist was really big, yet never a real option. Now I’m doing something where I can be a bit of both, which is just beautiful.

- How did this project come about? Were you already an existing group?

FABIAN: Max and I are old friends – we met in Bonn, because I think I replied to a Facebook ad that he wrote, citing Fairport Convention as an influence. When my band needed a new guitar player, I brought Max in – we kind of played a weird rap-rock crossover … It sounds pretty cringeworthy on paper, but we were quite good actually. Then a few years later, Max opened up for another band of mine. So yeah, we go way back, but that‘s the only connection I previously had with my bandmates in The Lindau Project.

MARCO: Jan and myself were already playing together in our band Apollo Papillon for about a year I think when he first told me about Max. Then I met him once in this café&bar-type place in Regensburg called The Couch; they were hosting a small concert and I was just about to leave when we got into talking about all sorts of music, from Minami Deutsch and Can all the way to Carole King. Once he’d mentioned the similarities of Engel der Gegenwart to China Cat Sunflower he had me hooked!

AMELIE: I got to know Max in my hometown’s theatre group, and it took me a while to realise that he’s also a musician. One day he spontaneously lent me his Waldzither (weird old-fashioned guitar-ish instrument) and I was so mesmerised playing on it for hours, that we got talking. And so he asked me if I’d like to join his ‘psychedelic pilot project’, and that sounded immediately amazing. I’d been kind of tired of performing solo, and looked forward to focusing more on sound and groove, instead of only witty lyrics accompanied by some basic guitar chords.

MAX: We teamed up this year for the occasion. When we started The Lindau Project I had never played music with Jan, Luis nor Marco before, although we know each other from the Regensburg music scene where they are involved in their respective musical projects, which I enjoy a lot. (about Amelie) With Amelie I play in a theatre group in Amberg; she is a wonderful cello player, and we also do some scenic music there together, so we just had to transfer that lovely musical interplay to The Lindau Project. Besides, she writes songs and tours around with her solo programme, and recently won a song slam award in Franconia. (about Fabian) Fabian is the only guy in the band whom I have known for a long time; about 10 years ago we both lived in the Cologne area, where we played together in a hip hop band, and later (or earlier?) in a folk rock band, both of which sadly faltered before the first scheduled gigs. It has always been such a joy playing with him, he plays very lyrically, not unlike Terry Cox or the recently deceased Gerry Conway, so when Fabian moved to Munich, I really wanted to get back to playing with him. This project was a perfect occasion for that.

- Can you tell me something about your ‘first contact’ with Popol Vuh?

FABIAN: My mom used to give me loads of cool films on DVD. We would watch them together and discuss them (we still do that, by the way). One of them was Fitzcarraldo – I must have been 17 or 18 then. So technically, that would have been my first contact with Popol Vuh: the amazing Werner Herzog movies. I bought the CD box set of the Herzog soundtracks that came out in 2010, I believe, and from then on I was hooked.

LUIS: For me it was actually Max reaching out about the project. I listened to a good amount of CAN, but had never heard of Popol Vuh. The connection to Amon Düül rang a bell, though.

AMELIE: I had never heard of Popol Vuh before Max invited me to the band. So my first times listening to it were quite analytical, checking out what I’d be singing. And wondering if I could deal with the high notes, which I luckily can. So now I’m suddenly really happy about those compulsory classical singing lessons at university, which I didn’t really like all that much. Now they have a whole new sense.

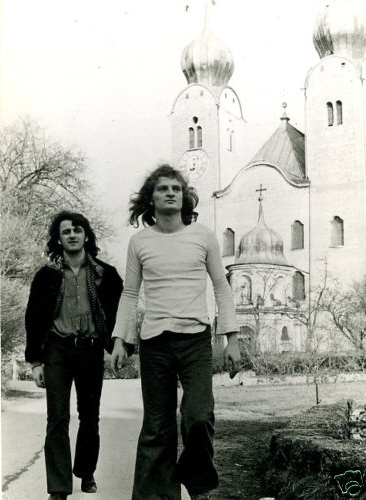

MAX: In 2017 my day job – which bears no relation with music – led me to an employment in Regensburg. For me it was a return to Bavaria, because I was born in the Pfaffenwinkel (between Munich and the Alps), although I just spent the very first years of my life there. After moving back, I immersed myself in all sorts of Bavarian culture – from traditional Alpine folk music via early music (e.g. the original Carmina Burana from Benediktbeuern) to Amon Düül II and Popol Vuh. Popol Vuh has since become an integral and invaluable part of my cultural conception of Bavaria. I could always make a point about why I see a specifically Alpine aspect to Popol Vuh’s music.

JAN: I was brought into this by Max and Marco and I started my journey into the world of Popol Vuh as the project began. So my first contact isn’t too far back. However, I am glad that I am only experiencing all of this for the first time and I feel like a younger version wouldn’t have enjoyed it as much. Five years ago I was convinced that rock music was dead and now I am finding so many new ideas in music that was written 50 years ago. It gives me loads of inspiration for my own songwriting and I like how much of it still lies ahead of me as I’m writing this. Getting into music is different when you have to play it afterwards and I’m glad that I dove in so deep right on.

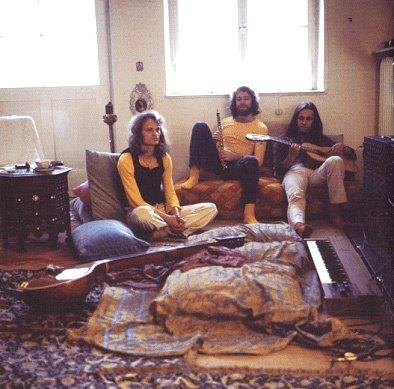

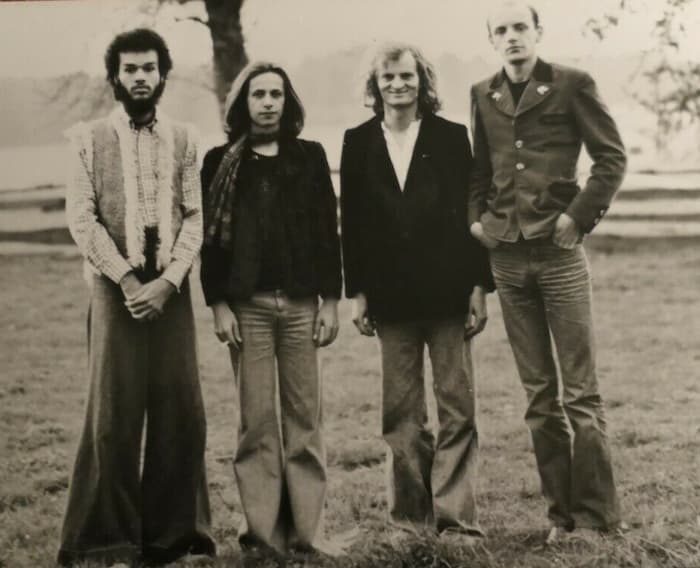

(From left to right: Jan, Marco, Max. Luis, Fabian, Amelie)

- What motivated you to devote a project to Fricke and Popol Vuh?

MARCO: Assuring that the music lives on, that it gets to meet new audiences. It’s sort of like getting out the watering can; somebody has to do it for Fricke’s garden to keep on growing. But part of it’s also to grow as a musician and turn new corners.

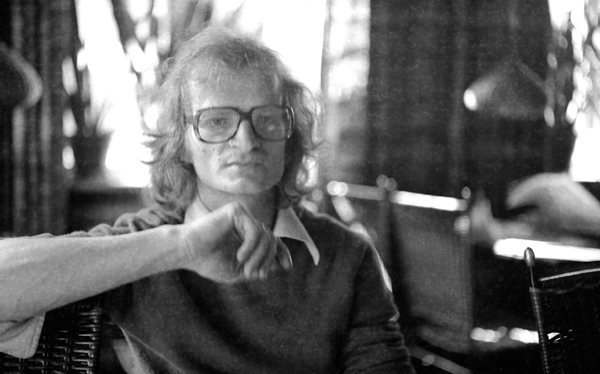

MAX: The short answer: Florian Fricke would have been 80 years old this year, and I think he deserves some sort of birthday party. The long answer: To me, Florian Fricke is one of the great European composers of the 20th century, who had that classical piano background, but who was always keen on integrating instruments such as the synthesiser and, later, the electric guitar into his work. Not as a gimmick, but as a serious instrument, on one equivalent level with the cello, the oboe or the piano. I was quite puzzled when I first visited the city of Lindau, because I naively thought there would be a street named after him, or some memorial plate on the house where he grew up, or even a bronze of his on the main square with an inscription of pure gold. I thought he’d be celebrated in Lindau at least remotely in the way that Beethoven gets celebrated in Bonn. But none of these assumptions held true. I still do not know anything at all about his upbringing in Lindau, and I hope I’ll learn more about it within this project. Meanwhile I thought: Let’s spread the word about Florian Fricke and Popol Vuh. And because I love playing the guitar parts on the Popol Vuh records, I thought: Why not find some people who feel some sympathy towards Fricke’s music, and play it together?

FABIAN: And I also feel like it’s quite a challenge to find that soft spot in between doing both of the things that Marco mentions - keeping Fricke’s music alive while turning new corners. Since Popol Vuh’s music was never really intended to be played live, we need to be creative and think outside the box most of the time. I think that’s how The Lindau Project transcends being a mere cover project.

- What do you consider to be the relevance of Popol Vuh’s music for today?

MARCO: What is expressed most clearly in such titles as Hosianna Mantra and Haram Dei: Fricke’s commitment to bridging musical and philosophical traditions, which, as I interpret it, seeks to redeem all those years we in the West have dismissed those traditions as cultural outsiders. And he wouldn’t limit himself to such constructs as Western and Eastern either - Agape, for example, brings up an ancient Greek concept of devotional love, then there are the numerous American indigenous influences all across his discography. Listening to how the music reflects these themes, you can tell that it is neither exploitative, nor patronizing or romanticizing, but accepts and appreciates those traditions as equal to our own. It’s like Allen Ginsberg putting Blake to music but using an Indian harmonium, or George Harrison’s work, for example with Ravi Shankar. Cultural dialogue of this sort really is crucial in preventing all kinds of fundamentalist, exclusivist, essentialist worldviews, even more so after the rise of globalization and related issues like the climate crisis that warrant a higher vantage point, a holistic understanding of our development as a species. It’s a form of genuine reciprocity.

LUIS: It's funny that all the guitar and drum tracks were tracked by one person [Danny Fichelscher] in the studio. This, I feel, resembles the modern production process more than other music of that time.

AMELIE: I love the experimental style, involving all sorts of unclean and chaotic sounds. As far as I know, it used to be really innovative back then, and still sounds weird to my ears now. So this is cool, because I always had this urge for innovation and for challenging listeners to wrap their ears around something unfamiliar.

MAX: To me, so-called rock music – in the sense of what we have seen in great concert halls and football stadiums during the last decades – has reached a dead end, or at least a point of severe crisis. The thrill is gone. When I visit a rock concert, most of the time my ears ring from the sheer loudness of the music, and the continuing musical references to the famous rock bands of the 1970-80s mostly bore me. For some months my ears rang so hard that I completely abandoned electric music and listened exclusively to 1930s archive recordings of unaccompanied European folk singing. Afterwards I asked myself whether the electric guitar (or other instruments that are commonly used in rock music) could serve a purpose outside of rock music. Popol Vuh’s music helps me tackle this question and provide an approach to how contemporary music could manoeuvre itself out of the aforementioned dead end. While Popol Vuh’s music utilises the techniques and instruments of rock music, I think that the musical substance is far away from being straightforward rock. The compositions owe more to classical music, as you can hear in Fricke’s piano demos, and it’s so exciting how, for instance, Danny Fichelscher transformed Fricke’s impressionist piano piece Garten des Pythagoras into Engel der Gegenwart, an energetic orchestra of jubilating electric guitars and splashing drums. It’s a bit like the glorious era between Renaissance and Baroque, around 1600-1620, with composers such as Praetorius, Schütz and O’Carolan. When you listen to Praetorius, you don’t know if certain compositions are serious classical works, or if he borrowed them from a jolly folk dance he encountered on a countryside walk, or if it was just a musical product made to provide for some entertainment and sonic luxury in the noble Baroque courts, similar to the modern idea of pop music. In Popol Vuh’s case the music sometimes simultaneously sounds like a Mozart piano piece, a Bulgarian folk dance tune and Wonderful Land by The Shadows, so I see a parallel there.

- How do you select the pieces for your project? Do you focus on a specific period of Popol Vuh’s activity?

MAX: It’s a spontaneous decision – whatever fascinates us, or makes any of us curious, we try. The early Moog compositions we don’t play because it would be boring for the guitar-playing fraction. Das Hohelied Salomos will celebrate its 50th anniversary next year, so we want to play some tracks from that period. Mark, a wonderful friend of ours from the UK, suggested we focus on the songs which have the most elaborate vocal parts, because he wants to hear Amelie sing as often as possible, and we’re quite convinced by his idea. This would mean that we concentrate on Fricke‘s 1970s output. Although we might tackle more of the 1980s material later, who knows. Spirit of Peace is an underrated cycle of musical pieces, of all things.

MARCO: I’d love to play sitar on one of the songs, so I hope we’ll get around to include Das Lied von den Hohen Bergen from Coeur de Verre, which is fortunately not too complicated. I’m really in awe of Al Gromer’s playing on Venus Principle, though!

- You use the term ‘re-imagining’. Great term. Can you go a bit into this concept? What are you doing when re-imagining a piece of Fricke’s?

MARCO: Once we’ve picked out a song, we listen to all the versions there are and try to work out the exact arrangements. After delegating those parts, it’s about what we can do to make the song reach that point it sets out to, though without merely treating it as an old dusty coat that you slip into. You don’t need to sing like Dylan to do his songs justice – in fact, you probably shouldn’t.

FABIAN: No one should sing like Dylan, not even Dylan himself. ;-)

AMELIE: I like Max’ relaxed way of guiding us through learning the songs, listening to the recordings at first and then making practical decisions along the way, in order to eventually find our own way of playing the songs convincingly. Since we are different people, in a different millennium, in a different situation, I would be absolutely out of this project if I’d have to imitate every note exactly as on the album.

MAX: ‘Re-imagining’ the music means that arranging this particular music for a stage setting is a creative process to us. We don’t want to be a tribute band, because that approach often attempts to look back into the past, specifically a past that it retrospectively glorifies, and maybe unjustly so; being in a tribute band would have a restricting attitude to it. I think we’d rather, figuratively speaking, see Popol Vuh’s compositions as our virtual contemporary companions, with whom we can build a relationship of our own, and together we can look into a musical future which is in some ways similar, albeit in other ways different to the musical past of the 1970s. This could also mean that at some point we’ll try to complete pieces that Popol Vuh haven’t finished - in our own way. Or that we arrange or compose other songs which have nothing to do with Popol Vuh, if we can make them fit in with the vibes. We may, for instance, throw in a Taylor Swift song for good measure, or whatever else tickles our fancy. Just the other way around of how US-American songwriter Meg Baird has added Popol Vuh‘s Last Days, Last Nights to her set, which otherwise mostly consists of self-penned songs. (Incidentally, it is the only instance of someone interpreting a Popol Vuh song live, without making a techno remix or something similar, to be found on YouTube.)

MARCO: Adding to that, I had the idea of interpreting an ancient Greek song I taught myself to play on the sitar. As far as I know, it’s considered to be the oldest song handed down in its entirety, words and music inscribed on a marble stele. While many have since recorded versions of it, an arrangement in the style of Popol Vuh, one that could bring it into the modern canon and breathes new life into the composition, is something I think Fricke would have loved to hear himself.

- What freedom or playground do you allow yourself in interpreting a composition?

MARCO: Sometimes it’s simply a matter of adjusting musical space, as with our extended solo in Steh Auf, Zieh Mich Dir Nach. But a far bigger part of it is instrumentation. The decision of adding the baritone guitar to make up for the lack of bass guitar in Popol Vuh’s arrangements is a brilliant example, I think that idea came from Max. Or me playing electric 12-string rather than acoustic, and through an old Yamaha rotary speaker cabinet for that cosmic chime. We also talked about combining different versions of songs and will probably try that with Engel der Gegenwart.

MAX: For instance, we take the liberty to sometimes sing zieh dich mir nach instead of zieh mich dir nach, changing the pronouns. (No, just kidding, we’re just confused.) It depends on the piece that we are playing. Some tracks – mostly those that seem to follow a clear-cut compositional template – call for a treatment close to the original arrangement, others feel like they invite us to jam a little bit, go slightly wild and fool around with them. (about Marco) Marco, for example, is such a lively and groovy rhythm guitarist, and his playing gives the music a swing and a danceability, so we enjoy going with that Mike-Heron-esque flow from time to time. Some aspects, however, we don’t want to change: for instance, we do not use a bass guitar because we take the lack of bass guitar to be a defining element of Popol Vuh’s music.

FABIAN: I feel like I’m quite a loose player anyway, probably because of my jazz background. Max recently said to me that my drumming is jazzier than Danny’s on the original recordings - that’s probably so deeply embedded into my style that I couldn’t switch it off even if I wanted to. Then again, I never abandon the rhythmical structures of the original. But I try to be playful inside those structures. And this is basically what we try to do as a group as well.

- What goal do you want to achieve with this project?

MARCO: I want an excuse to buy more records.

FABIAN: … and more records are always better than fewer records. ;-) I don‘t think any of us are looking for fame, please correct me if I‘m wrong – I‘d love to play live as much as possible, and also if we can introduce Fricke‘s music to some new people while satisfying old fans, that‘s about the nicest thing I can imagine: A big lovely group of music nerds!

JAN: I am indeed only looking for fame.

AMELIE: Haha, I would actually love to become famous! I’m just flexible in how I will achieve that, whether writing adventure novels or becoming a horse whisperer, at the moment and for the last 10 years music is my big thing and I am so so happy with this amazing band! It’s in fact the coolest band I’ve ever played in (said after only two rehearsals, but still, I really mean it), and after years of performing solo shows, my goal for this project is to make the most out of our possibilities of being 6 people with instruments!

MAX: I love churches as places of culture – independent of matters of belief and of institutionalised religion. Thus, I am sad that so many churches just fall to pieces and aren’t used in a contemporary way. You see, most villages in Germany – however small they are – have at least one little chapel, and most of these chapels have access to electricity, so any rural community could theoretically organise cultural events there, so long as the church administration is fine with it (and it should be!). This would enrich the cultural life in the countryside quite a lot. Churches are just terrific buildings, and most of the time they also have a wonderful natural reverb. I know, because I was in a Catholic high school … notabene they practised a fairly liberal catholicism there, which was good. We had a weekly mass, and as youngsters we played songs by Green Day and Focus there, both in our church and in neighbouring churches of various sizes. There I learned that each church has its unique reverb properties which you can explore as a musical ensemble. I think Popol Vuh’s music, which of course does have a spiritual aspect to it, fits especially well into these locations. Yeah, that’s what I want to achieve with it personally: I would love to add some beautiful European chapels and churches to our prospective tour calendar, which - of course - may also include more secular kinds of venues. And if the visitors of these concerts get inspired by the experience of the music and eventual synesthetic aspects (scent, wine or colours) just as I do, I’d be even happier.

FABIAN: Okay, maybe fame wouldn’t be too bad, you’re right. ;-)

- Popol Vuh often used religious texts or themes for the lyrics and song titles. And somehow the music itself often has a certain spiritual character or feel. Do you agree with that? Can you relate to this aspect?

MARCO: One of my courses at university addressed constructions of meaning in antiquity and, eventually, got me to research the Eleusinian Mysteries, which had been the most revered ritual practice in ancient Greece for over three centuries. From what I could gather from these studies, I think that Fricke had a good grasp on the nature of what he called “Urtexte”. These myriad origins of spirituality show quite clearly that there has not always been this strict dualism of sacred and profane, heaven and hell, body and soul, or “Gott und die Welt”, as a German idiom pithily has it. Such dogma is merely the hubris of permanence and built those towering religious institutions that primarily serve their own material interests. Instead, and I assume Fricke held a similar view, spirituality should be expressive of transcendence and transience because the divine transcends all – which is interesting in regard to music, being fundamentally transient with its temporal character and origin as a performing art. Materialist, consumerist, capitalist culture and even the enlightenment have only given us new Gods and people often don’t notice. But as Whitman wrote, “Logic and sermons never convince, the damp of the night drives deeper into my soul.” Music has the innate potential to be an element of that nocturnal dampness, to heighten personal spiritual insight and consciousness.

LUIS: I personally cannot relate to the spiritual and religious side of the songs. I don't know what the message is so I see it more as a mythological theme. Similar to dragons.

AMELIE: At first I didn’t really notice this aspect of Popol Vuh’s music, but now I’m actually happy about it. Thinking about this question, I realised that music has always been one of the main places (apart from rainbows and horses) where I could actually experience something divine in my world… While in my everyday life, things tend to turn grey from time to time, I am so grateful for the inexplicable spaces music has almost always offered me. Spaces where I can physically experience, through the vibrations, that there is so much more beauty in this world, and that I am so much more than my thoughts. Music has always been a shelter for me. So now, I am really curious to learn more about Fricke’s way of including religious traditions from different parts of the world into a new style of music…

JAN: I do not care too much about the spiritual side, however I cannot deny my catholic upbringing. Having spent many hours as a child in my village’s church with the organ playing at full ranks made me have a soft spot for a certain way in which Fricke's songs work. When I started out making music, my improvisations sounded a lot like these sacred melodies and I spent a lot of time trying not to make them sound like that. Now, as I study Fricke’s work, it is kind of ironic to see how he made a career out of something that I always tried to get rid of in myself. After all, it is part of my identity, no matter what.